Works on the North of Ireland

In memory of the hunger strikers: Sands Hughes O’Hara McCreesh McDonnell Hurson Lynch Docherty McElwee Devine

‘I can hear the curlew passing overhead. Such a lonely cell, such a lonely struggle.’ The Diary of Bobby Sands

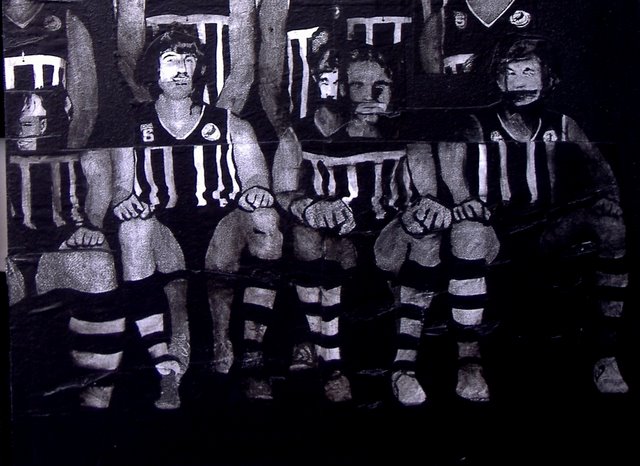

Northern Ireland, still an occupied state, requires/d British violence and containment to maintain its boundaries. This war on the people of the North of Ireland was/is fiercely resisted. These works are largely about the war fought in the terrain of prisons. It acknowledges the bravery and singularity of those that took part in the blanket and dirty protests and the hunger strikes.

By way of reminder, after the removal of political prisoner status, Republican prisoners demanded that the following be restored to them:

- The right not to wear a prison uniform;

- The right not to do prison work;

- The right of free association with other prisoners, and to organise educational and recreational pursuits;

- The right to one visit, one letter and one parcel per week;

- Full restoration of remission lost through the protest.

The British refused to grant these rights, although all were subsequently and quietly agreed to. Irish political prisoners escalated the protests to the point where 10 men died rather than submit to British criminalisation.

“I was only a working-class boy from a Nationalist ghetto, but it is repression that creates the revolutionary spirit of freedom. I shall not settle until I achieve liberation of my country, until Ireland becomes a sovereign, independent socialist republic” (Bobby Sands, quoted in IRIS, Vol. 1, No. 2, November 1981)

Prisons are sites of repression, surveillance, extra-legal violence and un-freedom. They may also become places of peer-to-peer mutual care and protection.

In the late 1970s and early 80s, Republican prisoners set up alternate systems of comradeship, mutual aid and learning – sharing tobacco, calling out warnings, leading lessons in Irish, sharing songs. This is mirrored in rotten jails across the world. Describing prisoner-to-prisoner learning sessions conducted in isolation units in the US, Russel Shoatz writes ‘Every Tuesday and Thursday …the Hole became an electrified classroom…we became a community whose commitment to one another went beyond our collective learning’ (I Am Maroon). These trusted peer-led learning spaces developed despite and because of the inherent violence of incarceration. Through developing their own self-help and self-defence brother-to-brother systems, imprisoned populations find their own ways of counteracting the threat of dehumanisation.

The ability to resist and maintain resistance takes place through peer support but also in a psychic refusal to submit. Huey Newton reflects on isolation units, or so-called soul breakers: ‘Soul Breakers exist because the authorities know that such conditions would drive them to the breaking point, but when I resolved that they would not conquer my will, I became stronger than they were. I understood them better than they understood me.’

Murder#4

Patsy O’Hara was the fourth prisoner to die during the 1981 hunger strikes. An INLA member, his body was brutalised after his death, as described here by Allen Feldman:

‘His corpse was found to be mysteriously disfigured prior to its departure from prison and before the funeral, including signs of his face being beaten, a broken nose, and cigarette burns on his body’.

This installation Murder#4 honours his resistance and dignity.

“I would rather die than rot in this concrete tomb for years to come” (Patsy O’Hara quoted in IRIS, Vol. 1, No. 2, November 1981)